Adil Ahmad gives you a glimpe into his inner world in this no-holds barred conversation with The Luxe Cafe, one of the very few interviews he ever agrees to. In his straightforward, amusing, self-deprecating manner, he speaks of everything from his childhood in a Raees family to his style which he defines as indigenous contemporary colonial, his reasons for bidding farewell to Good Earth, his obsession with symmetry and his pronounced distaste for blindly following trends. His star studded project list includes Vasundhara Raje’s New Delhi home, Saif and Kareena’s wedding, and the opulent Sujan Rajmahal Palace—but he believes that smaller spaces are far more challenging, like a miniature painting. Sneak a peek into Adil’s treasure-trove office at Jor Bagh and into the mind of the man who dropped out of school at 13 and got his first paid project at 16—a man who thinks nothing of giving his opinions out loud and believes that luxury is judicious affordability

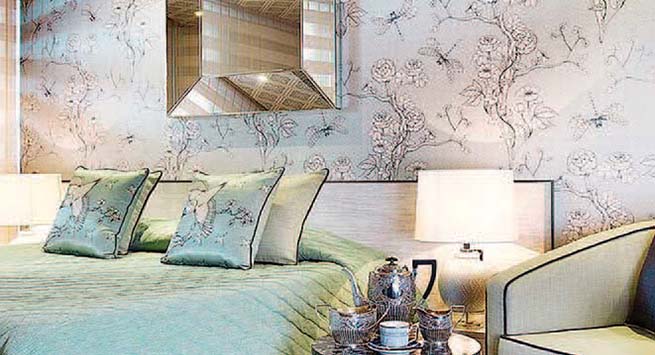

Walking into Adil Ahmad’s Jor Bagh office in New Delhi is a little like stepping into the Robbers Cave from Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves. Treasures unfold before your eyes in a madness of indulgence and you half expect the door to swing open to the sound of ‘Open Sesame!’ Rich red and gold wallpaper lines the walls of the main sitting area; a huge artwork in gold with embossed peacocks adorns the wall on the right, a chest with Chinese engravings sits smack in the center, baithak style sofas flank the room, the table is adorned with gorgeous brick-a-bracks that turn out to be meer-farshes from a bygone era—known as doorstops now, but historically meant to keep the chandni (floor spreads) in place, and even the air-conditioners are painted over in the base colour of the wallpaper. The room is lined with numerous photographs of Adil and his memories, lending an intensely personal touch.

It is, as Adil himself likes to call it, ‘contrived clutter’— mayhem of the meticulous sort.

In the midst of this canvas brimming with vibrance sits Adil Ahmad, founder of The Palace Collection, former Creative Director of Good Earth and interior designer par excellence, in a pristine white Jaipuri cotton kurta, block-printed all over with elephants. His simple sartorial choices speak of the man inside: honest, straightforward with an easy sense of humour and completely down-to-earth—which is especially remarkable given his list of high profile projects that include Vasundhara Raje’s New Delhi home, Saif and Kareena’s wedding reception, and the immensely opulent Sujan Rajmahal hotel. But Adil is also an intensely private man who prefers not to ‘drop names’ or speak of his clients, and absolutely detests having his picture taken. Much as we may love to photograph him amid his treasures, he refuses to be clicked. And he declares himself completely out of fashion, completely out of sync with the trends and competes with no one but ‘himself.’

“My first paid project was in 1993—when I was 16. So I always say now I’m at retirement age”

Perhaps all of this stems from the self-assuredness of the man who quit formal education and dropped out of school at the age of 13—when he was in eighth standard. “I’ve always been aesthetically inclined,” he explains, “When I was young, other children would go to toy stores but I gravitated towards stores with magazines of interiors and literature. I was a big reader and read a lot about historical books from a very young age, and it was a natural progression that grew into what it is today.”

“I never looked at it as a profession. I was in Doon School Dehradun, and I decided in class eight to drop out of school. I used to ask my mother, why am I here? And her reply was that the family has always been there—your father, your grandfather— and I said that’s not a reason for me to be doing it! I hate to do things on a bell! And one fine day I just dropped out. The last I formally went to school was in 1990.”

Even more surprising than the above facts is the revelation that he did his first paid project at the age of 16. “I started working very early,” he says. “My first paid project was in 1993—when I was 16. So I always say now I’m at retirement age! I’ve been working 24 years.” Yes, the sense of humour pervades everything that Adil Ahmad speaks about.

“Now interior designing is the ‘it’ thing to do, it’s a very fashionable profession. Every bored star wife, everyone who has nothing better to do has become an interior decorator!”

But did he have any formal training in interior design? Not in the least. And he’s very vocal about his opposition to such ‘training’, too. “Today everything has become a course or a diploma. Now interior designing is the ‘it’ thing to do, it’s a very fashionable profession. Every bored star wife, everyone who has nothing better to do has become an interior decorator! Back then it wasn’t something people had even heard about. I was aesthetically inclined but didn’t even know there was such a thing as interior design! Luckily we had a large house in Lucknow so I could potter about there and one thing led to another.”

He goes on to narrate an amusing anecdote about the whole question of where he did his ‘training from’: “Some time ago, a fancy university called me to give a talk. They asked me what is the discipline you grew up with, and I said: Nothing— I’m the most indisciplined person, I dropped out of school! They said you’re not supposed to say that! Then they asked where did you train in design from? I said, I don’t believe in training because it curbs creativity. And so after the 3-day seminar they were just happy to be rid of me!”

This disarming, self-deprecating humour is perhaps just as beautiful as Adil’s designs. He speaks of the reactions of his family— elite, wealthy and Cambridge-educated— who could not imagine such a thing as a drop-out interior decorator son. “My elders used to say: ye to ghaas khodega! (he’ll just be a grass cutter). In the early stages when I used to say I’m an interior designer, my grandafather who loved me a lot, used to tell me beta don’t say all these bekaar ki baatein (utter nonsense). Just say you do nothing. Say you’re from a Raees (elite) family and you don’t need to do anything! Apne ghar ka khaate ho!”

“My elders used to say: ye to ghaas khodega! (he’ll just be a grass cutter) In the early stages when I used to say I’m an interior designer, my grandafather used to tell me beta don’t say all these bekaar ki baatein (utter nonsense). Just say you do nothing. Say you’re from a Raees (elite) family and you don’t need to do anything! Apne ghar ka khaate ho!”

But times have changed and how. Accolades and recognition have poured in at Adil’s doorstep. And yet, he doesn’t believe in being trendy or up with the times. In the era of pared-down décor, Adil’s work is a riot of colour, texture and imagination. Does he consciously shun minimalism to swim against the current?

“Minimalism, to our Indian sensibility, is an alien reality,” says he. “We are not Sweden, not Holland. India is all about surface decoration. Starting from Mohenjo Daro to Ajnta Ellora, the Mughal palaces, the Red Fort, the Golden Temple—you name it— all religious places carry surface decoration. So that’s what I carry forward—lots of surface decoration, indigenous handiwork. We have absorbed so many cultures. What is Indian culture? It’s a diaspora of cultures that have come together—Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs, Christians and Parsis and so on. I’m not trying to make something that is royal or chic or posh. It’s just a collection of beautiful things put together.”

“It’s not about expensive things, it’s about a well-lived space which tells that you’ve been on a journey—you’ve travelled.”

He points out each beautiful object adorning the room around him—the trunk from China, the embossed peacocks artwork from Bhutan, a brass plate on the table from Moradabad, marble meer farshes made in Rajasthan. “It’s not about expensive things, it’s about a well-lived space which tells that you’ve been on a journey—you’ve travelled. It’s not that one fine day I’ve gone and bought something from a particular designer in say, England. Sadly, that’s what’s happening today: we walk into homes and they just look like showrooms. There’s no personal touch because sadly today people are not in touch with their own realities. They are just trying to ape another person or what they perceive is ‘it’.”

He tells you that sometimes clients come to him and ask what’s in fashion? “I tell them I don’t know, I’m the least in fashion—look at me!”

The self-deprecating charm comes into play again as he cracks jokes at his own expense. “Look, my kurta is pure cotton, brought from the Dastkar shop in Ranthambhor. It’s cheap, it’s cheerful, it’s cool and suits our Indian climate! I couldn’t stuff myself into Dolce & Gabbana. I mean that’s amazing stuff but I know I would look like a gargoyle in it!” he guffaws.

“Today, we walk into homes and they just look like showrooms. There’s no personal touch because sadly people are not in touch with their own realities.”

But then he turns philosophical. “It’s just a question of being in touch with your reality and being comfortable with yourself. Every day I wake up and I don’t think I’m doing anything lofty—I’m just doing a job—like everyone else. I’m not tripping on my success. There’s no great epiphany I get while sleeping at night! Today there this whole thing of ambition and everyone’s driven by social barometers. How many projects, how many lakh square feet, this client and that project. I’m in it for myself. One shouldn’t take oneself so seriously.”

So does he prefer indigenous arts and crafts, ethnic designs and weaves? “I like contemporary Indian design. My sensibility is grounded in Indian design, but in a contemporary idiom. Design or style cannot remain petrified; it has to move with the times. Mine is an indigenous, contemporary colonial style. When Lutyens created the Rashtrapati Bhawan, he gave the columns to Indian architecture. But the dome was inspired by the Sanchi Stupa and the huge verandahs cater to the Indian climate. So it is a very organic mixture.” He points to the sofa he sits on and continues, “Now this is a European sofa but in a Baithak style. Otherwise sofas were not Indian. You always had the chandni or the carpet where you sat— and these are the meer farshes used to keep the carpet down. When Europeans started using them they became door stoppers. Here they were supposed to keep the sheets from blowing off. Similarly, the shama daans were made to keep the breeze from blowing the candles off. In Europe there were all closed rooms so there was no need for them. Design is constantly evolving, so we don’t need to be purist about it.”

“Mine is an indigenous, contemporary colonial style. When Lutyens created the Rashtrapati Bhawan, he gave the columns to Indian architecture. But the dome was inspired by the Sanchi Stupa and the huge verandahs cater to the Indian climate. So it is a very organic mixture”

But ethnic is not his style, and he’s not making a conscious effort to revive indigenious crafts. “With all due respect, I’m not a revivalist! I’m not Laila Tyabji who revived Indian textiles. I’m nothing so lofty— I just make do with what’s available.”

So what are the three most significant things he keeps in mind when designing spaces? “Texture, pattern and symmetry,” he states. “I’m obsessed with symmetry. I’m very much into texture and layers.” His love for symmetry is very evident in his own office space—but is there a particular reason for this penchant? “I don’t know! Maybe it’s because I have such a convoluted life that in some aspect you want clarity of thought, clarity of space! You know when someone gives me a gift I think—oh, I wish they’d given me two! I’d rather not have a gift than have just one!”

But then, his primary design principle is to let the space reflect its inhabitants. “I never want a project to reflect me. I like it to reflect the clients’ personality. I like to coax, cajole, interpret a client’s sensibility—not impose my own.”

And is there a particular décor item that is his favourite? “I collect carpets,” he states, but explains further. “When I design I take something as the centrepiece. For instance, in this room I began with the carpet —it has texture, it has pattern , it has patina, it has a certain age to it—so I designed around it. But in the end, it depends on the unique sensibility of the client—they might have a painting, a textile, a chandelier, or a light. It could be a colour, a sensibility, a place. I’m not hung up on that.”

“I’m obsessed with symmetry. I’m very much into texture and layers.”

But then it’s not just homes that he designs, but heritage and boutique hotels too, like the famed Rajmahal Palace. What’s the design style he follows for a hotel? His answer is typically sassy and straight. “By God’s grace, I haven’t allowed myself to be bastardised by commercialism. I don’t take on big hotels. And if I do take on big hotels, they’re bespoke hotels, so I have the luxury of creating bespoke spaces. Whether it is a home or a hotel, for me they’re the same.

No project is ever too difficult, but he feels that more than the large spaces, it’s the really small ones that are the most challenging. “If you ask me doing up this little office of 900 sq feet was far more challenging than something of 90,000 sq feet. Everyone today talks in terms of lakhs of square feet, but the smaller the project the more challenging it is. It’s just like a miniature—creating everything to the minutest detail.”

“Adil has taken on a heritage hotel in Nepal and a ‘very interesting project’ at a coffee estate in Coorg. “I just finished a heritage hotel in UP, too which was a colonial bungalow. Plus I keep doing homes in and around Delhi.”

“For instance, in this room I wanted space for 8-10 people to sit and so everything had to be calculated. The space between the chair and table is exactly 1 inch. You go 2 inches more you can’t walk out the door! It looks like clutter but there’s always a method to it. There are exactly 12 pictures here, exactly the same angel on all sides, candle placed the same way, coasters placed at exactly the same place! There’s a method to this madness! It’s what I call contrived clutter.”

And all this ‘madness’ would soon be directed to his upcoming projects—but he’s extremely tight-lipped about them. All he will concede is that he’s taken on a heritage hotel in Nepal and a ‘very interesting project’ at a coffee estate in Coorg. “I just finished a heritage hotel in UP, too which was a colonial bungalow. Plus I keep doing homes in and around Delhi.” And that’s all he will say on the subject. But he explains why: “I dislike it terribly when I’m written about vis a vis other people and clients. It trivialises me and my work. Today it’s become fashionable to drop names and I think that you’re not sure of yourself if you’re doing that.”

He doesn’t believe in formal collaborations either, which he refers to as ‘arranged marriages’!

“I was the Creative Director of Good Earth in the past… but these Arranged marriages, you know,” he chuckles. “It was a great journey, Mrs Lal and I are extremely good friends. But I think creativity and commercialism don’t go together. When we parted ways, Good Earth had a different trajectory. They were changing the course from being a bespoke design house to more of a commercially viable store—like a crate and barrel. So that’s where the dichotomy was. I thought it was better to remain individual, and I do not franchise my brand, because I would lose control over it. I’m a very small fry in the larger scheme of things. But I like the freedom— I like to touch and feel my projects.”

“Mrs Lal and I are extremely good friends. But I think creativity and commercialism don’t go together. I thought it was better to remain individual, and not franchise my brand, because I would lose control over it. I’m a very small fry in the larger scheme of things.”

Adil does act as consultant to other brands and designers but in a “very loose, informal” way. “They take me on to design one home, or one collection. I’m working with builders but I don’t do 15 row houses for them. I do one house, what they do with it is their concern. “

But he does work with designers he admires. “I love working with other designers particularly with Viya Home. Vikram Goel does amazing, cutting edge design in metal. Then there’s also Beyond Designs. But it’s not a tight collaboration.” Internationally, the designers he loves are Alberto Pinto, Moroccan designer with his atelier in Paris, who passed away a few years ago. “He did everything from planes to boats to palaces to homes—very unusual work. Then there’s Jacques Garcia, too. They inspire me but their style is unique to their sensibility; I cannot interpret that in Indian idiom.”

As far as Indian designers are concerned, he says, “In the Indian sensibility there’s sadly no one I can think of because everyone I see is trying to ape an alien reality. I liked Susanne’s place—she had imported very nice lights, but can I get that whole interior? I can’t. Abu-Sandeep do good work, they use nice products, interesting techniques.”

For now, he’s going off on his two month summer vacation—one of the perks, he says, of owning your freedom. What’s his ideal vacation style? Pat comes the reply: “Being able to not think—to be blank.”

“In the Indian sensibility there’s sadly no designer I can think of (who I admire) because everyone I see is trying to ape an alien reality.”

“For me it’s not the destination, it’s more about the people you’re with and where you’re comfortable. One of my favourite cities in the world is London. I like the pace of life in England, the design, the whole cultural aesthetic.”

But he surprises you by declaring himself a ‘boring person’ who neither drinks, no smokes, nor parties. “I’m not one for nightlife or for the night spots! I’m not a party person, I’m quite a square, boring: I don’t smoke, or drink—or even serve drinks. I don’t fit into the stereotypical image of the designer.”

“I’m not a party person, I’m quite a square, boring: I don’t smoke, or drink—or even serve drinks. I don’t fit into the stereotypical image of the designer.”

“At one interview,” he reminisces “I was asked what is the one thing you never leave home without—and I showed them my tasbih (prayer beads)! They asked me what is your favourite car and I told them I don’t know how to drive! As long as it’s comfortable, it’s air-conditioned, what does it matter?”

So, truly, what does he consider as luxury, then? His answer is most astonishing. “Affordability!” he laughs. “What sways me is affordable luxury—judicious affordable luxury. I don’t buy fabric for more than Rs 600 a metre. I wouldn’t go into a fancy store and buy fabric for Rs 3000 a metre—I don’t wear clothes for that much!” he guffaws again. “I do totally affordable stuff—I’m just glad it gives a luxe look!”

“People just give me all these labels of ‘royal’ and ‘rich’ and all this s**t !” he exclaims. “But have u seen how the royals live, half of them?” He stops short then, and exclaims rather impishly, “God I should be careful what I’m saying!”

“What sways me is affordable luxury. I don’t buy fabric for more than Rs 600 a metre. I wouldn’t go into a fancy store and buy fabric for Rs 3000 a metre—I don’t wear clothes for that much! I do totally affordable stuff—I’m just glad it gives a luxe look!”

On a more serious note, he reiterates, “Why would I want to create China or Versailles or Buckingham Palace in an Indian home? My style is influenced by the homes we grew up in. I grew up in a house designed by an English Architect in the late 30s. My grandfather was India’s first Indian Chief Justice in British times. So it was an amalgamation of the two cultures.”

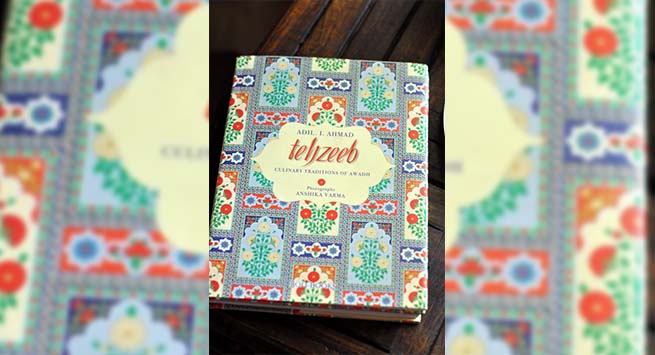

His pride in his heritage is evident from the book he has written on the Culinary Traditions of Awadh, titled Tehzeeb—which he now hands me as a parting gift. Tehzeeb, which means culture (or literally, politeness and sophistication), is steeped in the history of Lucknow, displaying magnificent photographs of not just the dishes whose recipes he describes, but also of his home, his family and history entwined with nuggets of the lifestyle of the opulent in Awadh, and the ornate architecture of the city.

“Today colonial has got bastardised as ‘Raj’ or something foreign. But it is imbibed into the Indian sensibility. I mean who’s to tell what’s Hindu art? Or what is Indian culture? It is an amalgamation of so many diverse streams.”

And suddenly he waxes eloquent on serious social issues like intolerance. “Today we’ve become so intolerant of differences. I think it should be about celebrating differences. Celebrating difference of opinion. See this room—these are kundalini paintings based on Tantric art, the cushion covers are Turkish, these prints from Rajasthan, this is an Iranian carpet from Samarkand. Success is a journey. The day you stop growing or moving is the end. You plateau.”