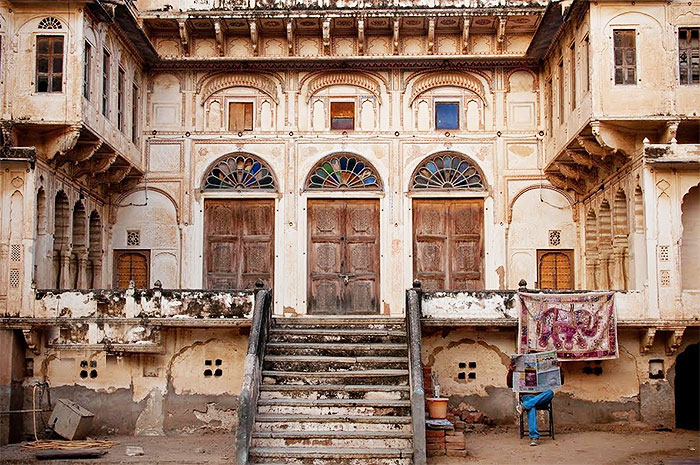

This pictorial feature on Mandawa highlights the diversity of heritage and traditional aesthetics in India. While training the lens towards the arid Shekhawati, what emerges is a vibrant hot-spot of colour, carvings, creative inspirations and historic inclinations, called Mandawa. Explore the hamlet of Mandawa, in all its forms imprinted with the frescoes of time, as it blends together the past and the present in an optimistic view towards the future

Emerging out of the philosophy of cha-no-yu (the tea ceremony) in fifteenth-century Japan, wabi sabi is an aesthetic that urges one to look for and imbibe the beauty in things imperfect, impermanent, and incomplete.Writer-artist and an exponent of wabi sabi, Andrew Juniper notes that “if an object or expression can bring about, within us, a sense of serene melancholy and a spiritual longing, then that object could be said to be wabi-sabi.”

Filtered through the ever-widening of lens of wabi-sabi, we can see Mandawa as a landscape full of vivid signposts harking back to an age past and of one that is still ‘becoming’.

“The tides of time should be able to imprint the passing of the years on an object. It is the changes of texture and colour that provide the space for the imagination to enter and become more involved with the devolution of the piece. Whereas modern design often uses inorganic materials to defy the natural ageing effects of time, wabi sabi embraces them and seeks to use this transformation as an integral part of the whole. This is not limited to the process of decay, but can also be found at the moment of inception, when life is taking its first fragile steps toward becoming.” ― Andrew Juniper writes in Wabi Sabi: The Japanese Art of Impermanence. And this is the very spirit embodied in the hamlet of Mandawa, the highlight of Shekhawati and the must-visit base for an all-Shekhawati junket.

Once the trading route to Arabian Sea from northern plains of India, the Shekhawati region houses one of the most profusely abundant concentration of frescos in the world. Situated in the north-east of Rajasthan, the region witnessed blossoming of trade and with that came the merchant communities spending on building ornately decorated family residences (Havelis), as a symbol of their wealth, which also became the embodiment of Shekhawati’s art. These rich merchants commissioned artists (mostly potters) to paint their residence with murals and mirror-work. Later, with migration of the indigenous merchant families (Marwaris), the havelis suffered from abandonment and many of them dimnsihed with age and neglect. Today, the lens has turned back on them as the lushly painted, intricately carved, forts and havelis of Shekhawati, restored to their past glory are major tourist attractions of Rajasthan.

In Shekhawati, frescoes were brought in by Shekhawat Rajputs in their forts and palaces. The region has been recognised as the ‘open art gallery of Rajasthan’ with the kaleidoscopic havelis and imposing fort facades. In these havelis and forts, there are doorways, lintels, brackets, gargoyles, pillars, walls which have frescoes depicting scenes from Hindu mythology, landscapes and sceneries. The walls are studded with exquisite mirror work, but the ceilings are the cynosure for all eyes. In all, the forts and havelis of Manadwa offer a glimpse to this storybook town of a bygone era.

The beautiful wall paintings that decorate the havelis of Mandawa in Rajasthan, India, have seen the themes changing over the years. While mythology dominated the themes of the frescoes in the earlier days, portraying local legends, animals, portraits, hunting and wrestling scenes, etc., the19th century saw scenes reflecting the British (Raj) influence with paintings of cars, trains, balloons, telephones, gramophones, and portraits of English men in hunting gear and immaculately dressed haveli owners.

Shekhawat Rajputs built forts in all their thikanas. Mandawa Fort was built by Thakur Nawal Singh Bahadur in 1755. It is perhaps the best place to discover the legacy of Shekhawati is from inside the Castle Mandawa, a fortress now converted into a luxurious heritage hotel which, in the manner of many historic homes, is an interesting blend of the old and the new. Medieval turreted towers, palanquin-roofed balconies, co-exist here with modern amenities kitted out in rooms which spell old-world charm. Family portraits, antique cannons and arms add to the charm of this family-run resort where old world hospitality and warmth of tradition still reigns.

The fort’s zenana (women’s quarters) has various rooms offering different themes. One room has antique murals, another has a marble fountain, while the turret room boasts of walls that are 7 feet (2.1 m) thick. Diwankhana, the formal drawing room, is decorated with family portraits and an array of antique armour, while the colonial verandah accommodates the bar. There are nooks and niches for one to seek out, even as the luxury of traditions handed down continues to surround the traveller whose eyes feast on this rich art-studded panorama, prodded on by the modern day guardians of the past.

Trailing through the pictures above, if you feel tempted to see this desert beauty, to feel its ancient rhythm and bask in its serene moorings, tucked away into the heart of time – so still, yet breathing full – then take off on a Shekhawati sojourn to Mandawa.