Vikram Goyal, founder of product and interior design firm Viya Home, and co-founder of organic wellness brand Kama Ayurveda, speaks to The Luxe Café about his desire to celebrate Indianness in an international language. In this exclusive in-depth conversation, Goyal talks about his love for creating glamorous spaces that are international but interspersed with touches of India—a style reflected naturally in his home at Shanti Niketan, New Delhi. His luxury interior projects are spread across New Delhi, Mumbai and Chennai to New York and London, including bespoke pieces for Christian Louboutin’s Men’s stores in London and New York—and has collaborated with names like Kelly Hoppen in London. But he insists that luxury could be even a gadda or a cushion, for luxury is to be comfortable in your own space, in your own skin. True luxury, he says, is that of the mind.

Vikram Goyal likes to create spaces that are “glamorous and comfortable—modern and international, with a touch of India.”

That line pretty much defines the design aesthetic of Viya Home, the interior and product design firm founded by Goyal. It’s the aesthetic that pervades his designs across myriad luxe projects in Chennai, Mumbai and New Delhi, residences and penthouses in New York, and the most recent award-winning home in Goa. It runs through all the products and collections created by Viya Home—products that grace not just homes but also stores of designers like Tarun Tahiliani and Rohit Bal, or a bespoke brass bench for the Christian Louboutin Men’s stores in London and New York.

What’s more, it also perfectly encapsulates the aesthetic of his own place in New Delhi’s Shanti Niketan.

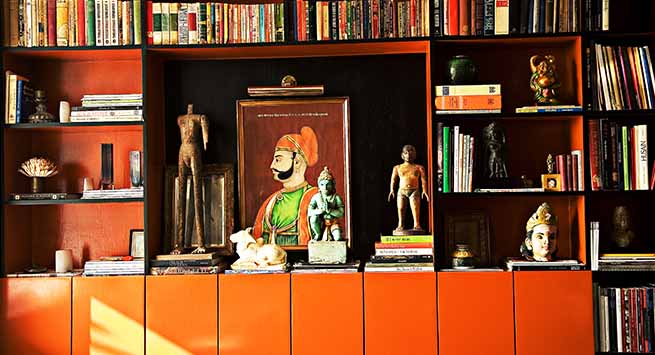

Our conversation takes place on the second floor of his house, in a large room peppered with ethnic artefacts picked out from possibly every corner of India, interspersed with contemporary products created by his own brand. From the sea-horse shaped brass door handle at the entrance to the brocade upholstered sofas in the centre, from the malachite inlaid brass stools to the rows of calligraphic mirrors lining the walls, from the giant vahana statues handpicked from South India to the bright red heirloom chandelier, the room is an eclectic image of Vikram’s words brought to life: glamorous and comfortable, modern and international—with major displays of India. The all- pervasive element in the room that jumps out at you, though, is the extremely liberal use of brass. But then that is to be expected, since brass is the primary material in almost all of Viya Home’s collections.

“Our workshops are primarily with brass,” says Vikram. “I find brass to be the most dextrous, malleable, easiest metal to work with. Copper you can’t mould, I don’t like stainless steel because it’s a new material and bronze is only used in casting, typically.” Gesturing towards the brass finials and tables, he continues, “All this is made in sheet metal, so one important factor is the material’s versatility. There are a variety of techniques and processes available to work with brass—reposse, hammering, casting, welding—to name a few. Secondly, I love the colour: first it’s gold, then it tarnishes into a more bronze colour, so you can do different varieties of it. We love the multiple finishes that can be applied to it: gold, silver, bronze and Verdi gris.” And he adds in a split second—“Unlike stainless steel, it also goes back to our roots!”

“I find brass to be the most dextrous, malleable, easiest metal to work with… it also goes back to our roots.”

This involvement with the “roots” has been a defining factor in Vikram’s work—even his career. Having studied development economics at Princeton University, Vikram worked with Morgan Stanley as an investment banker. Soon, however, he was beckoned by the roots, and returned to India. Back in India, the first project that he applied his creative energies to was the wellness brand Kama Ayurveda, which he co-founded with Vivek Sahni, Rajshree Pathy, Vikram Goyal and Dave Chang. Kama Ayurveda was followed by Viya Home.

“When I came back to India I wanted to work with something that was indigenous and had excellence,” says Vikram. “So the first idea was Ayurveda. How could international packaging and branding pick an Indian idea and take it to the wider world? The second project became Indian craftsmanship. How do you take Indian craftsmanship and use modern design and a modern language to describe it and take it to a wider world? That was followed by the interior design part, several years into product design. It was more about how you develop an international language celebrating Indianness.”

He explains further, “We wanted to be an indigenous design voice that would dispel the idea of Made in India being ‘cheap and cheerful’ and hold its own internationally. It was axiomatic then that with Made in India, we work with multi-generational skilled artisans to revive traditional craft techniques and bring our designs to life. Our initial inspirations were completely Indian with motifs and ideas drawn from elements of traditional Indian art, culture, and architecture: the lotus, the cow, the banana leaf, patterns, finial sculptures, arches, domes. ”

The “we” in his statement refers to him and his sister Divya Goyal, whose names merge together to form the ‘Viya’ in Viya Home. Divya handles the business part of the brand while Vikram is the creative driving force. And while Viya Home was created to celebrate Indianness, Vikram emphasises that there is no singular modern Indian sensibility when it comes to design.

“You can celebrate Indianness in a variety of ways—through the forms, materials, colour, textures—people have such a huge dictionary of references to choose from. If you look at the interior magazines of 15-20 years ago, people like “Mapu” Martand Singh—one of the great pioneers in reviving Indian textiles—his home was very simple with terracotta and beautiful Indian prints. From there to something like this,” he points to the black marble flooring of the room, “where I’ve used black, a very urban New York kind of material, not something you would associate with a country like India and then these sofas covered in brocade—which don’t necessarily look Indian but kind of oriental.”

The brocade for the sofas was created in Benaras but meant for Bhutan— for the country’s traditional attire. But this kind of heavy texture brocade is inherently a tradition of Italy, says Vikram, indicating the rich Jacquard. “It is very much a part of what you saw in old French palaces and palazzos.” Brocade, however, is also an integral part of the Indian tradition— particularly the kimkhwab brocade that invariably comprises the trousseaus of Indian Muslim brides.

Interestingly, the calligraphic mirrors lining the walls of a portion of the room, off to one side, have their origins within the homes of the Bohra Muslim community from Gujarat. Inscribed with Quranic verses and names of spiritual figures, the mirrors lend a fascinating, steeped-in-history-feel to the room, especially as they stand side by side with bell-shaped brass finials from Viya Home that are very ancient-Indian-temple in their design. On the opposite corner in the same room are rows of brass bowls, again in-house, with quintessentially oriental designs of waves, clouds, dragons and the like. A confluence of several cultures in one space.

“Among the Bohra Muslims in Gujarat you have these very heavily decorated, very ornate buildings, very lived,” explains Vikram of the mirror origins. “Sebastian Cortez has photographed the place—their homes are decorated with wooden carved ceilings and carved panels. Even in Kashmir you have that heritage of wooden carvings and ornamentation—that’s where the whole idea of ornamentation came from: the wealthy merchants. In Jaisalmer too, those big ornate havelis belong to the merchants. This is a tradition of art and architecture across India in a variety of forms.”

But that tradition somehow isn’t a part of the reality of Indian homes today, rues Vikram. “Today I find that the architects and designers barely reference these traditions—at least at the very high end. To them being modern is being straight-lined, with shades of browns and greys.”

He gives you the example of Brazil, where modern homes have their own local material, their own interpretation of what is modern. “In India, though, I think we’re so used to— because of colonial heritage—blindly aping what is western. We Indians have always lived around noise, so we’ve had no minimalistic influences in Indian living. Everything has embellishments here. Look at our clothes, look at our food—so spicy! We’re not monastic at all.” The architectural genius of Indian structures built in the yesteryears is something missing from the present age. A distinguishing factor, a stroke of uniqueness, a ‘point of view’, as he calls it: “You’ve had people like Charles Correa who was rooted in India so his works stand out. If you look at all the other people who did work in the 50s, 60s and 70s in India, they all had a point of view. Which new building has come up in recent years that has a point of view? Not a single interesting modern building. The last one was the Lotus temple—the Bahai temple. But beyond that there’s no iconic building that you could point to and say: arrey go and look at it!”

“Not a single interesting modern building has come up which has a point of view”

What about contemporary Indian hotels? Are there any that he would consider well designed? “Well, The Lodhi (Delhi) is unique but I find it too cold… very Stalinist. I love the Umaid Bhawan (Jodhpur) but it was designed long back. There’s Ahilya By The Sea in Goa—very charming, a series of cottages—very beautiful. I prefer more of the heritage properties, though: Devigarh, Raas Johdpur, even Narain Niwas in Jaipur. I love what they did with the flooring in the Manor hotel. Beautiful, some Italians did it.”

On the subject of flooring, Vikram’s preferences are primarily Indian. “There are very few people I know who would do woodwork and floorings in Indian marble,” he says, while emphasising his own preference for it, evident from the flooring in his own house. “In this house, there are so many different kinds of Indian marble. White, black, pink Makrana. But only a handful of people nowadays use Indian marble. They may use other stones like Kota in the more functional areas.”

His ardour for Indian craftsmanship is most fascinatingly incorporated into their Celestial Tables collection which showcases semi-precious stones inlaid in metal. “In the Taj Mahal, you typically find semi-precious stones inlaid into marble, but we started inlaying them into metal. Malachite, lapis and so on inlaid in brass. It’s a technique we developed and created handles, tables and all with it.” That one, incidentally, is also his favourite signature collection.

“We’ve done so many, some 30 designs in this,” he enumerates. “We started with the romantic tables—the lotus tables and tables shaped as different flowers, then it moved on to more Art Deco ones and now to the more abstract ones—such as that scribble table on the right. That really chalks out our whole progression as a design team.”

That, interestingly, is the Viya Home evolution: from creating products quintessentially Indian in form and structure, to products that are Indian in craftsmanship but largely international in form.

“Over the years, our markets widened internationally, and now we’re working through Italian soft furnishings firm Dedar, which presents our collections to architects and designers in Europe and the Middle East. So our products are no longer Indian in form. For instance, the fish scale pattern is very Indian, and so are these lotus tables and the stupa-shaped tables. But we don’t do that anymore. Now we have other things like the big consoles which are not very Indian at all. We began with more romantic India modern, then the more structured symmetrical, now the more abstract, very modern. ”

“In the Taj Mahal, you typically find semi-precious stones inlaid into marble, but we started inlaying them into metal. Malachite, lapis and so on inlaid in brass.”

What brought on this change, though, since he started off trying to bring in the Indianness in an international way? “I grew a bit tired of it!” he laughs. “Funny, no? I started celebrating it. But now, to me, it’s more creative, more interesting to do things that are not totally Indian.” However, he keeps the Indianness intact in other ways, such as the texture, the material and the craftsmanship. “The designs are modern but the texture and material is very Indian.” He emphasises.

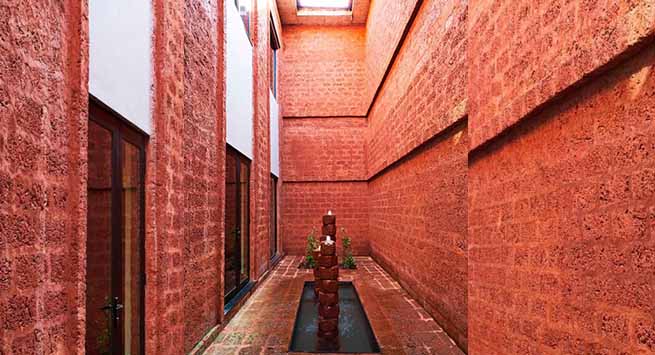

Among his interior décor projects though, there is still the subtle translation of the modern Indian aesthetic. Particularly so with his latest project in Goa, where he is building large, single family homes. “In Goa we’re working with local architects and local materials. We’re building homes and trying to create a modern Indian aesthetic in that domain.”

Interestingly, Viya Home’s very first interior projects were two apartments in Chennai, almost completely in contrast with each other. The first one was for a friend of Vikram’s. “She saw my house and loved it,” he reminisces. “She has an interest in many things from Tanjore paintings to Tibetan panels and also wanted it very black and dramatic. But the other house was completely the opposite. The person wanted something much more serene, tropical and quiet and influenced by Art Deco. So while one is almost complete sensory overload, if you will, the other is completely calm and serene.” And that is how he prefers his work to be—unique, non-repetitive.

And when he works upon a space, what are the most important aspects he takes into consideration?

“One is the spatial arrangement. How you will place the furniture and accessories and how will people move.” He points across the room, towards the small clusters of sofas and chairs—conversation places. “For example, over here I have very consciously given four conversation places. Most people would not give four places, but I prefer the conversation to be in smaller groups. A lot of people would have chalked it out like one big thing or done it into two. A lot of people do socialise in this panchayati style,” he chuckles. “But I like smaller groups and I find people that I have over to my house also like conversation in smaller groups.”

Most people prefer the large single style, and he narrates how a client expressly asked for it. “One client came to me and said that’s the way we live. So I had to then very creatively design the living room where it didn’t look like a panchayat!” he laughs.

The second most important thing, points out Vikram, is lighting. He illustrates this through his own space yet again. “If you notice,” he gestures, “there’s no overhead light here. Most people like the places over-lit. Mine is all warm yellows and very full of ambience. The lampshades here are a very European thing. In India we had the light coming out through glass (chandeliers), but that becomes harsh. However, these were designed for candles, which gave a very soft warm glow. But now you’ve got to get the soft glow through fabric.”

“In a city home you’re more constrained but in a place like Goa, to think of spaces together, the volumes, the proportions together, that was most challenging.”

“The third thing is what beautiful objects do we have? Because without beautiful objects or furniture, you’re not going to get a great room. In the end it’s really about the art and the objects.” Vikram’s designs showcase perfectly how art and objects come together cohesively to create a space that’s striking yet co-ordinated. Viya Home collections are spun around myriad fascinating themes, from celestial and galactic to ancient architectural, encompassing pyramids, the acropolis and so on. The sculptural and architectural acropolis console is one of Vikram’s favourite pieces. Their abstract, captivating wall sculptures and sconces in brass reveal an almost fluid structure.

But among all his interior projects, the most challenging one yet was the most recent. “The Goa house was the most challenging as we wanted to use local material in a very modern way.” An award-winning work of art, the Goa home is where Vikram worked with a local architect. Exposed concrete ceilings, extensive use of laterite—even for the fountains—use of local stone such as Kadappa and Machala and a pervading raw, sensual vibe mark the Goa home.

“In a city home you’re more constrained but in a place like Goa, to think of spaces together, the volumes together, the proportions together, that was most challenging. But there’s more scope for creativity. That’s the most interesting and in a way difficult—to use local material, and to use it cleverly in a fresh way.”

Among all his designed spaces though, his favourite is still his own. “My own space, because I could take risks. I also spent the most time on this—my first project when I was not an interior designer. A lot of heart and soul went into this! I wanted it to be very masculine. Therefore the black edges, the black floors etc. And if you notice in the corridors, it’s very busy. I love Indian art and artefacts and I wanted to celebrate that.”

“Real luxury is to be able to do what you want, dress the way you want— it doesn’t have to be expensive. It’s just that you have the confidence”

Vikram also collaborates with other designers like Vinita Chaitanya and Adil Ahmed for his projects, while fashion designers like Tarun Tahiliani and Rohit Bal collaborate with him to create a number of accessories for their stores. “They come to us, tell us what they want—the look and feel, and we propose ideas to them.” One such idea translated into a “masculine, art-deco inspired” bespoke bench for Christian Louboutin Men’s stores in London and New York. Among his international collaborations, there is of course Dedar, the Italian interior décor and soft furnishings major. “Dedar are one of Italy’s top fabric manufacturers. They represent their own fabrics, they sell their fabrics created for French luxury brand Hermes, and they sell our products.”

And yet, despite all the grandeur he likes to create, despite his luxe projects and high profile clients, his idea of luxury is far removed from price tags and brand labels. “Real luxury,” he articulates, “is to be able to do what you want, dress the way you want— it doesn’t have to be expensive. It’s just that you have the confidence; a luxury of mind. It’s a luxury of when you’re secure in a particular way,” he continues. “When you’re not trying to impress the Joneses. Luxury could be just a gadda and a cushion! But it means being comfortable in your own space… Otherwise everything else is contrived. So it can be that you’re speaking from a position of so called material or physical wealth where it doesn’t matter.”

“People want things which are thought through and organic,” he says. “There’s a heightened sense of sophisticated luxury nowadays, which has nothing to do with money, but with purity and integrity.”

So which are the Indian and international interior designers whose work speaks to him?

“Internationally, there’s the Milan based Dimore studio, and Paris based Persian designer India Mahdavi. Both of them use colour and forms in a very creative way. There are a number of great design firms based in Paris and London. We work with people like Kelly Hoppen, a very well-known London based designer.” Kelly Hoppen, interestingly, was ranked by the Daily Telegraph as the second most influential female interior designer in Britain, in the year 2014.

“There’s a heightened sense of sophisticated luxury nowadays, which has nothing to do with money, but with purity and integrity.”

Among his Indian favorites, Goyal enumerates Adil Ahmad and Sameep Padora—founder of the Mumbai-based architecture studio sP+a; some of the work of Bijoy Jain and some works of Sandeep Khosla in Bangalore.

But ask him for décor advice and he wittily responds: “That’s like asking someone, what should I have for dinner? People ask me what’s the design trend and I ask them what’s the food trend ?” he chuckles. “If you’re health conscious or environmentally conscious, or you like Indian food…. it all depends on your preferences. There is no set décor trend as such. But largely speaking, internationally, it has moved towards the celebration of colour, where there are interesting styles coming together and a celebration of the old and new mixed together. Otherwise everyone was doing grey and simple, clean and people’s styles were getting indistinguishable. All were looking like clones of the same.”

The trend of vibrant, differentiated décor is percolating to India too, he says, but not enough. “Someone like Adil’s aesthetics are so interesting, so over the top. And such a strong point of view, too” he points out. Internationally, though, the change was led by designers in Europe. “All these designers based in Europe— Paris, London and few in Milan, a few in America too, they said, we’re going to voice our creations in a unique way. So you see some great stuff coming out— great houses and restaurants and some really interesting lovely spaces. And hotel owners are also encouraging them to speak with a unique voice, because otherwise if you see the old Marriotts and Four Seasons and they all looked identical to each other—they all looked like first class airport lounges—minimal, clean and all the same! At least now people are saying they want to be different—and thank god for that!”